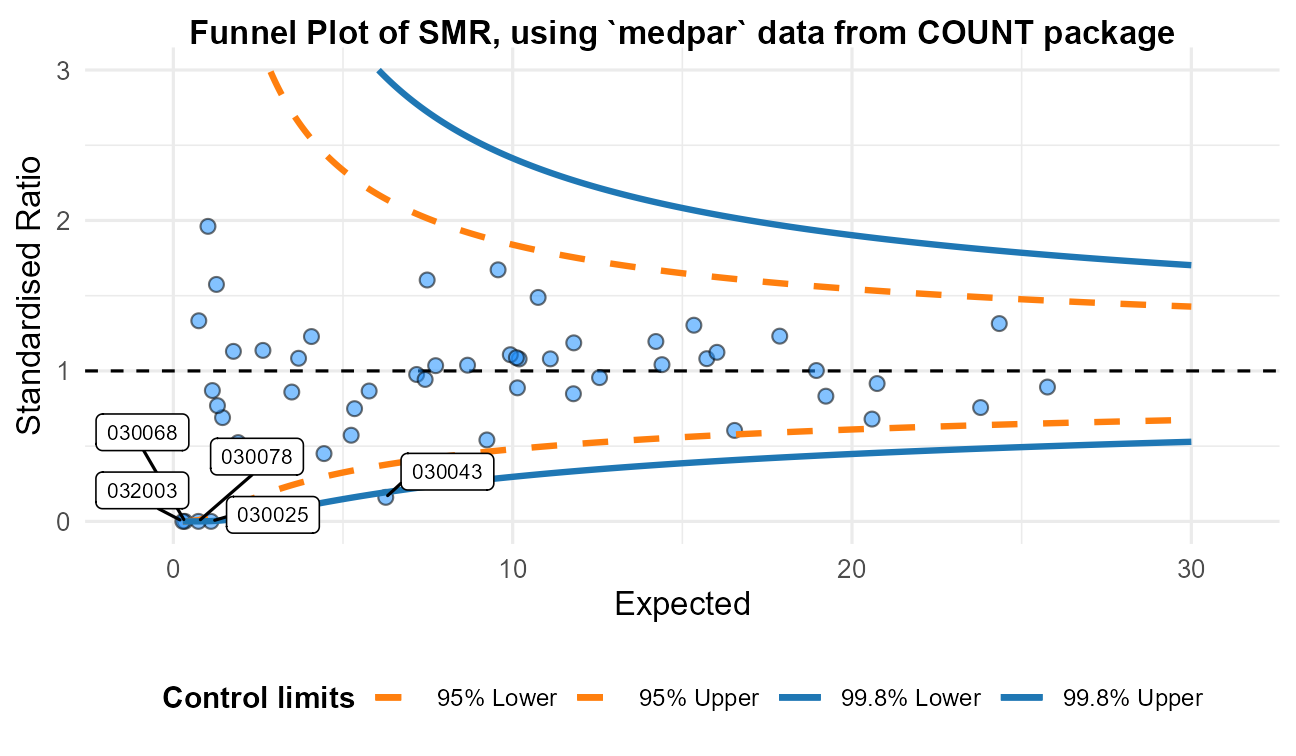

class: title-slide ## Understanding Standardised Mortality Ratios (SMRs) <br> .pull-left[ ### SHMI and HSMR <br><br><br><br> ### <img src="./assets/img/crop.png" alt="Mainard icon" height="40px" /> Dr Chris Mainey <svg viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;position:relative;display:inline-block;top:.1em;fill:#005EB8;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M459.37 151.716c.325 4.548.325 9.097.325 13.645 0 138.72-105.583 298.558-298.558 298.558-59.452 0-114.68-17.219-161.137-47.106 8.447.974 16.568 1.299 25.34 1.299 49.055 0 94.213-16.568 130.274-44.832-46.132-.975-84.792-31.188-98.112-72.772 6.498.974 12.995 1.624 19.818 1.624 9.421 0 18.843-1.3 27.614-3.573-48.081-9.747-84.143-51.98-84.143-102.985v-1.299c13.969 7.797 30.214 12.67 47.431 13.319-28.264-18.843-46.781-51.005-46.781-87.391 0-19.492 5.197-37.36 14.294-52.954 51.655 63.675 129.3 105.258 216.365 109.807-1.624-7.797-2.599-15.918-2.599-24.04 0-57.828 46.782-104.934 104.934-104.934 30.213 0 57.502 12.67 76.67 33.137 23.715-4.548 46.456-13.32 66.599-25.34-7.798 24.366-24.366 44.833-46.132 57.827 21.117-2.273 41.584-8.122 60.426-16.243-14.292 20.791-32.161 39.308-52.628 54.253z"></path></svg> [@chrismainey](https://twitter.com/chrismainey) <svg viewBox="0 0 496 512" style="height:1em;position:relative;display:inline-block;top:.1em;fill:#005EB8;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M165.9 397.4c0 2-2.3 3.6-5.2 3.6-3.3.3-5.6-1.3-5.6-3.6 0-2 2.3-3.6 5.2-3.6 3-.3 5.6 1.3 5.6 3.6zm-31.1-4.5c-.7 2 1.3 4.3 4.3 4.9 2.6 1 5.6 0 6.2-2s-1.3-4.3-4.3-5.2c-2.6-.7-5.5.3-6.2 2.3zm44.2-1.7c-2.9.7-4.9 2.6-4.6 4.9.3 2 2.9 3.3 5.9 2.6 2.9-.7 4.9-2.6 4.6-4.6-.3-1.9-3-3.2-5.9-2.9zM244.8 8C106.1 8 0 113.3 0 252c0 110.9 69.8 205.8 169.5 239.2 12.8 2.3 17.3-5.6 17.3-12.1 0-6.2-.3-40.4-.3-61.4 0 0-70 15-84.7-29.8 0 0-11.4-29.1-27.8-36.6 0 0-22.9-15.7 1.6-15.4 0 0 24.9 2 38.6 25.8 21.9 38.6 58.6 27.5 72.9 20.9 2.3-16 8.8-27.1 16-33.7-55.9-6.2-112.3-14.3-112.3-110.5 0-27.5 7.6-41.3 23.6-58.9-2.6-6.5-11.1-33.3 2.6-67.9 20.9-6.5 69 27 69 27 20-5.6 41.5-8.5 62.8-8.5s42.8 2.9 62.8 8.5c0 0 48.1-33.6 69-27 13.7 34.7 5.2 61.4 2.6 67.9 16 17.7 25.8 31.5 25.8 58.9 0 96.5-58.9 104.2-114.8 110.5 9.2 7.9 17 22.9 17 46.4 0 33.7-.3 75.4-.3 83.6 0 6.5 4.6 14.4 17.3 12.1C428.2 457.8 496 362.9 496 252 496 113.3 383.5 8 244.8 8zM97.2 352.9c-1.3 1-1 3.3.7 5.2 1.6 1.6 3.9 2.3 5.2 1 1.3-1 1-3.3-.7-5.2-1.6-1.6-3.9-2.3-5.2-1zm-10.8-8.1c-.7 1.3.3 2.9 2.3 3.9 1.6 1 3.6.7 4.3-.7.7-1.3-.3-2.9-2.3-3.9-2-.6-3.6-.3-4.3.7zm32.4 35.6c-1.6 1.3-1 4.3 1.3 6.2 2.3 2.3 5.2 2.6 6.5 1 1.3-1.3.7-4.3-1.3-6.2-2.2-2.3-5.2-2.6-6.5-1zm-11.4-14.7c-1.6 1-1.6 3.6 0 5.9 1.6 2.3 4.3 3.3 5.6 2.3 1.6-1.3 1.6-3.9 0-6.2-1.4-2.3-4-3.3-5.6-2z"></path></svg> [chrismainey](https://github.com/chrismainey) <svg viewBox="0 0 448 512" style="height:1em;position:relative;display:inline-block;top:.1em;fill:#005EB8;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M416 32H31.9C14.3 32 0 46.5 0 64.3v383.4C0 465.5 14.3 480 31.9 480H416c17.6 0 32-14.5 32-32.3V64.3c0-17.8-14.4-32.3-32-32.3zM135.4 416H69V202.2h66.5V416zm-33.2-243c-21.3 0-38.5-17.3-38.5-38.5S80.9 96 102.2 96c21.2 0 38.5 17.3 38.5 38.5 0 21.3-17.2 38.5-38.5 38.5zm282.1 243h-66.4V312c0-24.8-.5-56.7-34.5-56.7-34.6 0-39.9 27-39.9 54.9V416h-66.4V202.2h63.7v29.2h.9c8.9-16.8 30.6-34.5 62.9-34.5 67.2 0 79.7 44.3 79.7 101.9V416z"></path></svg> [chrismainey](https://www.linkedin.com/in/chrismainey/) <svg viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;position:relative;display:inline-block;top:.1em;fill:#005EB8;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M294.75 188.19h-45.92V342h47.47c67.62 0 83.12-51.34 83.12-76.91 0-41.64-26.54-76.9-84.67-76.9zM256 8C119 8 8 119 8 256s111 248 248 248 248-111 248-248S393 8 256 8zm-80.79 360.76h-29.84v-207.5h29.84zm-14.92-231.14a19.57 19.57 0 1 1 19.57-19.57 19.64 19.64 0 0 1-19.57 19.57zM300 369h-81V161.26h80.6c76.73 0 110.44 54.83 110.44 103.85C410 318.39 368.38 369 300 369z"></path></svg> [0000-0002-3018-6171](https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3018-6171) <svg viewBox="0 0 496 512" style="height:1em;position:relative;display:inline-block;top:.1em;fill:#005EB8;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M336.5 160C322 70.7 287.8 8 248 8s-74 62.7-88.5 152h177zM152 256c0 22.2 1.2 43.5 3.3 64h185.3c2.1-20.5 3.3-41.8 3.3-64s-1.2-43.5-3.3-64H155.3c-2.1 20.5-3.3 41.8-3.3 64zm324.7-96c-28.6-67.9-86.5-120.4-158-141.6 24.4 33.8 41.2 84.7 50 141.6h108zM177.2 18.4C105.8 39.6 47.8 92.1 19.3 160h108c8.7-56.9 25.5-107.8 49.9-141.6zM487.4 192H372.7c2.1 21 3.3 42.5 3.3 64s-1.2 43-3.3 64h114.6c5.5-20.5 8.6-41.8 8.6-64s-3.1-43.5-8.5-64zM120 256c0-21.5 1.2-43 3.3-64H8.6C3.2 212.5 0 233.8 0 256s3.2 43.5 8.6 64h114.6c-2-21-3.2-42.5-3.2-64zm39.5 96c14.5 89.3 48.7 152 88.5 152s74-62.7 88.5-152h-177zm159.3 141.6c71.4-21.2 129.4-73.7 158-141.6h-108c-8.8 56.9-25.6 107.8-50 141.6zM19.3 352c28.6 67.9 86.5 120.4 158 141.6-24.4-33.8-41.2-84.7-50-141.6h-108z"></path></svg> [www.mainard.co.uk](https://www.mainard.co.uk) ] .pull-right[ <br><br> <img src="understanding_SMRs_files/figure-html/funnel-1.png" width="100%" /> ] .footnote[Presentation and code available: **https://github.com/chrismainey/understanding_standardised_mortality**] ??? Say hi - introduce myself I'm Patient Safety Lead - System Analysis and Delivery with NHS England and Improvement. I'm analyst by background, specialised in statistical modelling and and machine learning methods. My previous role was with UHB - HED, providing HES-based analytical tools to ~50 NHS trust and other organisations. Specialised in statistical productions, mainly risk adjustment and prediction focused. Today we are going to talk about monitoring mortality, the construction of standardised ratios, the common SMRs in use SHMI and HSMR, cross-sectional and longitudinal monitoring, and issues. A bit of theory, a bit of anecdote. Some R scripts available to show some of the functions. --- # Measuring death ### Why do we do it? + 'Smoke alarm for the quality of care' - <a id='cite-keoghKeoghReviewHospital2013'></a>(<a href='#bib-keoghKeoghReviewHospital2013'>Keogh, 2013</a>) + Tacit assumption that high mortality is bad -- ### Does it work? + __Yes:__ + Increases power of comparison by reducing confounding. + Monitoring them has effects on hospital's vigilance and culture <a id='cite-jarmanMonitoringChangesHospital2005'></a><a id='cite-wrightLearningDeathHospital2006'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7487.329'>Jarman, Bottle, Aylin, et al., 2005</a>; <a href='https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.99.6.303'>Wright, Dugdale, Hammond, et al., 2006</a>) + __No:__ + Poor proxy of avoidable death: <a id='cite-girlingCasemixAdjustedHospital2012'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/f4fr3b'>Girling, Hofer, Wu, et al., 2012</a>) + Case-mix adjustment can exaggerate biases it tries to address: <a id='cite-deeksEvaluatingNonrandomisedIntervention2003'></a>(<a href='#bib-deeksEvaluatingNonrandomisedIntervention2003'>Deeks, Dinnes, D'Amico, et al., 2003</a>) --- class: middle ### Desceptive argument: ___"...of course we should be monitoring deaths"___: - but is this too simplistic a view? Is it a measure of 'quality?' --- class: inverse middle # Crude Mortality --- ## Crude mortality Rate .pull-left[ + Count the numbers of deaths? - Not a rate {{content}} ] .pull-right[ <img src="understanding_SMRs_files/figure-html/crudeplot-1.png" width="100%" /> <img src="understanding_SMRs_files/figure-html/crudetime-1.png" width="100%" /> ] -- + Give it some sort of scale: proportion + In hospital, patients, discharges, bed-days etc. + Often adjusted to a larger standard, e.g. per thousand `$${Crude\ Rate(p)} = \frac{\Sigma Deaths}{n}$$` {{content}} -- + __Strengths:__ + Easy to calculate + Directly linked to real deaths {{content}} -- + __Weaknesses:__ + Not really comparable across organisations + Case-mix confounds rate --- class: inverse middle # Standardising mortality ### Aim: reduce confounding and increase power of comparison --- ## Direct standardisation + Take our data and map them to a common population/structure. + Example: Age-standardisation: + Calculate age-specific rates in groups (e.g. 10-year bands) + Identify a relevant standard population in corresponding groups. E.g. [European Standard Population]( https://www.opendata.nhs.scot/dataset/standard-populations) + Multiply age-specific rates by standard population bins + Sum and adjust to desired multiplier (e.g. per 100, per 100,000 etc.) + Commonly used in public health cases, such as cancer incidence and mortality rates. -- + __Strengths:__ + Directly comparable between units/group/sites/countries + Does not require statistical model -- + __Weaknesses:__ + Harder to relate to local/observed numbers + Challenging to do for anything more than age and sex --- ## Indirect standardisation + Compare our data to expected averages + E.g Calculate average rate, per-patient, across the dataset + Per trust, calculate 'expected rate': `\(average\ rate * n\)` + Present as grouped ratios of Observed / Expected -- + Commonly uses a regression model + Predict risk of event, based on case-mix factors (predictors) -- + __Strengths:__ + Directly comparable between units/group/sites/countries + Usually require statistical model, e.g. regression {{content}} -- + __Weaknesses:__ + Usually requires a statistical model, e.g. regression to calculate 'expected rate' + Susceptible to more forms of bias <a id='cite-iezzoniRisksRiskAdjustment1997'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/c2trv4'>Iezzoni, 1997</a>; <a href='#bib-deeksEvaluatingNonrandomisedIntervention2003'>Deeks, Dinnes, D'Amico, et al., 2003</a>) + Can be challenging to understand what changes in rates mean --- ## Example SMR: .pull-left[ ```r # Load 'medpar' dataset from COUNT package. data("medpar") # build logistic regression for risk of death mod1 <- glm(died ~ los + factor(type) + age80 , data=medpar , family = "binomial") # Predict risk of death back into data frame. medpar$pred <- predict(mod1, type="response") # SMRs medpar %>% group_by(provnum) %>% summarise(Observered = sum(died), Expected = sum(pred), SMR = sum(died) / sum(pred)) ``` ] .pull-right[ ``` ## # A tibble: 54 x 4 ## provnum Observered Expected SMR ## <labelled> <int> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 030001 16 19.2 0.832 ## 2 030002 19 20.7 0.916 ## 3 030003 2 1.77 1.13 ## 4 030006 23 25.8 0.893 ## 5 030007 2 4.44 0.451 ## 6 030008 5 9.24 0.541 ## 7 030009 4 5.34 0.749 ## 8 030010 22 17.9 1.23 ## 9 030011 12 12.6 0.955 ## 10 030012 12 7.48 1.60 ## # ... with 44 more rows ``` ] __SMR = 1: observed=predicted, >1: observed>predicted, <1: observed <predicted__ --- class: inverse middle # Common (indirectly standardised) SMRs: ### Summary Hospital-level Mortality Indicator (SHMI) ### Dr Foster Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio (HSMR) --- ## Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio (HSMR) + Work in USA as early as 1970s demonstrated ability to calculate theses metrics. + Prof. Sir Brian Jarman and others adapted these methods to English health care system, data coding standards and structures. + Methods were heavily impacted and applied in aftermath of Bristol and Mid-Staffs enquiry. + Controversy on some issues: + Commercial exploitation of method by Dr Foster Intelligence - accused of 'black box methods' + University of Birmingham and others published criticism + Imperial rebutted criticism, and won NIHR funding to build national monitoring system + Until recently, sent alerts to CQC and trusts for high mortality. __Key References:__ + Original paper: <a id='cite-jarmanExplainingDifferencesEnglish1999'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/fkkfm9'>Jarman, Gault, Alves, et al., 1999</a>) + Birmingham's criticism: <a id='cite-mohammedEvidenceMethodologicalBias2009'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/bv4sh8'>Mohammed, Deeks, Girling, et al., 2009</a>) + Paul Taylor's long-form article on history and controversy: <a id='cite-taylorStandardizedMortalityRatios2014'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/f5pxfw'>Taylor, 2014</a>) --- ## Summary Hospital-level Mortality Indicator (SHMI) With growing controversy, then NHS Medical Director, Prof. Sir Bruce Keogh, commissioned a review. -- Recommended creating a new, NHS owned and transparently published indicator, however: + Changed the remit to in-hospital or within 30-days of discharge + Applied to all acute activity (except still birth) + Cruder case-mix model deliberately to avoid controversial measure such as: + Palliative care coding + No adjustment for deprivation - political context + Co-morbidity score 'binned' rather than continuous to reduce change of gaming + Fewer, larger diagnosis groups -- __Key References:__ + Review: [National Quality Board (in national web archives)](https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20120503091458/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Qualityandproductivity/Makingqualityhappen/NationalQualityBoard/DH_102954) + Sheffield paper: <a id='cite-campbellDevelopingSummaryHospital2012'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/gb3r9t'>Campbell, Jacques, Fotheringham, et al., 2012</a>) + NHSD SHMI: <a href="www.digital.nhs.uk/SHMI">www.digital.nhs.uk/SHMI</a> --- class: center ## Case-mix factors: <img src="./assets/img/model.png" alt="SHMI & HSMR comparison table"> --- # Criticisms (HSMR and/or SHMI) + Link to quality of hospitals unclear, + For: <a id='cite-cecilWhatRelationshipMortality2020'></a><a id='cite-cecilInvestigatingAssociationAlerts2018'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819619847689'>Cecil, Bottle, Esmail, et al., 2020</a>; <a href='https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007495'>Cecil, Bottle, Esmail, et al., 2018</a>) + Against: <a id='cite-lilfordUsingHospitalMortality2010'></a><a id='cite-blackAssessingQualityHospitals2010a'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/frq62g'>Lilford and Pronovost, 2010</a>; <a href='https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2066'>Black, 2010</a>) + They do not directly relate to avoidable death <a id='cite-hoganAvoidabilityHospitalDeaths2015'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/f4fr3b'>Girling, Hofer, Wu, et al., 2012</a>; <a href='https://doi.org/10/gb3swm'>Hogan, Zipfel, Neuburger, et al., 2015</a>) + Single number does not convey nuance + Insensitive to who patients who survived + Susceptible to 'gaming' - <a id='cite-hawkesHowMessageMortality2013'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f562'>Hawkes, 2013</a>) + Covid-19 pandemic, these models assume stability + Case-mix adjustment fallacy (<a href='https://doi.org/10/bv4sh8'>Mohammed, Deeks, Girling, et al., 2009</a>) + Constant risk fallacy <a id='cite-nichollCasemixAdjustmentNonrandomised2007'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/bv4sh8'>Mohammed, Deeks, Girling, et al., 2009</a>; <a href='https://doi.org/10/d7f9jh'>Nicholl, 2007</a>) + Potential for Simpsons paradox <a id='cite-marang-vandemheenSimpsonParadoxHow2014'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003358'>Marang-van de Mheen and Shojania, 2014</a>) --- class: inverse middle # Cross-sectional --- # Comparison at single point in time .pull-left[ + Both HSMR and SHMI report on the final year of their modelling period. + Snapshot of performance against expected + League-tables are bad, as measure is relative <a id='cite-goldsteinLeagueTablesTheir1996'></a><a id='cite-lilfordUseMisuseProcess2004'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/chf9kj'>Goldstein and Spiegelhalter, 1996</a>; <a href='https://doi.org/10/c97xd2'>Lilford, Mohammed, Spiegelhalter, et al., 2004</a>) + SPC principles applied in using funnel plot <a id='cite-spiegelhalterFunnelPlotsComparing2005'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/fq7z8t'>Spiegelhalter, 2005a</a>) + Overdispersion ] .pull-right[  ] --- # Overdispersion .pull-left[ ___Overdispersion___, where conditional variance is greater than conditional mean, occurs when: 1. Aggregation / Discretization 1. Mis-specified predictors/model 1. Presence of outliers 1. Variation between response probabilities (heterogeneity) {{content}} ] -- __Repeated measures (correlation) __ + Regression assumes all points independent + Sampling from same organisations repeatedly + Clustered: - local means -- .pull-right[  ] --- # Dealing with overdisperion + Ignore it: use-case dependent. False alarm rate too high here, as error is underestimated + Improve the model with more information: Some room for this. + Build a model with clustered assumption <a id='cite-maineyStatisticalMethodsNHS2020'></a>(<a href='https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10094736/'>Mainey, 2020</a>): + Quasi-likelihood methods (with multiplicative scale factor) <a id='cite-wedderburnQuasiLikelihoodFunctionsGeneralized1974'></a>(<a href='#bib-wedderburnQuasiLikelihoodFunctionsGeneralized1974'>Wedderburn, 1974</a>) + Compound distribution model: beta binomial <a id='cite-skellamProbabilityDistributionDerived1948'></a>(<a href='#bib-skellamProbabilityDistributionDerived1948'>Skellam, 1948</a>) + Random-intercept model: model 'within' and 'between' variance + Apply tools based on meta-analysis methods: <a id='cite-spiegelhalterStatisticalMethodsHealthcare2012'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/dqpqpk'>Spiegelhalter, Sherlaw-Johnson, Bardsley, et al., 2012</a>) + Designed to summarise studies fo different size + Akin to hospitals of different sizes + Additivity assumption - more like random-intercept than scale factor --- class: inverse middle # Longitudinal --- # How? .pull-left[ + Can't simply plot in XmR chart, as risk-adjustment forms denominator (and overdispersion) {{content}} ] .pull-right[ <p style="text-align:center;"> <img src="./assets/img/agg_cusum.gif" alt="Aggregate cusum chart" width = "400" height="200"> <img src="./assets/img/person_cusum.gif" alt="Person-level cusum chart" width = "400" height="200"> </p> ] -- + Can use the observed and predicted in risk-adjusted control chart {{content}} -- + Common is 'risk-adjusted CUSUM' + Continuous log-likelihood ratio test {{content}} -- <br> `$$C_t = max(C_{t-1} + w_t, 0)$$` + `\(C\)` CUSUM value at time-point `\(t\)` (e.g. a monthly at a trust) + `\(w\)` is a weighting, in this case the log-likelihood ratio (observation v.s. England) to calculate the CUSUM weight/value ( `\(C\)` ) at time point ( `\(t\)` ) --- # Differences in CUSUM methods Until recently, mortality outlier programme and Imperial college sent monthly alerts to Trusts. .pull-left[ ### CQC - (aggregated) + Data are transformed to z-scores + Overdispersion adjustment based on additive model (<a href='https://doi.org/10/dqpqpk'>Spiegelhalter, Sherlaw-Johnson, Bardsley, et al., 2012</a>) + Can convert average run-length to FDR, and set threshold <a id='cite-griggNullSteadystateDistribution2008'></a><a id='cite-carequalitycommissioncqcNHSAcuteHospitals2014'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/bgvkdx'>Grigg and Spiegelhalter, 2008</a>; <a href='#bib-carequalitycommissioncqcNHSAcuteHospitals2014'>Care Quality Commission, 2014</a>) + Global trigger (5.48) - set to marginal 0.01% FDR. + Applicable to other indicators and groupings, subject to same transformation ] -- .pull-right[ ### DFI/Imperial - (person-level) + Binomial assumption and threshold set through simulation of average run-length to false positives. <a id='cite-bottlePredictingFalseAlarm2011'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/cbr4rq'>Bottle and Aylin, 2011</a>) + Unique to each trust / group / reporting period. + Intractable to calculate each month, and authors fitted a set of descriptive equations give a decent approximation for conditions where mortality rate 30% or lower. + Formula can then be solved through optimisation methods and give threshold value for each group. ] --- # Problem with CUSUM charts + A common criticism of CUSUMs is that the are opaque and hard to interpret + What does the CUSUM value mean? -- .pull-left[ ### Variable Life-Adjusted Display (VLAD) + Originally used to visualise surgical outcome more intuitively <a id='cite-lovegroveMonitoringPerformanceCardiac1999'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/dtsvbg'>Lovegrove, Sherlaw-Johnson, Valencia, et al., 1999</a>) + Can actually add limits to plot using cusums <a id='cite-sherlaw-johnsonMethodDetectingRuns2005'></a>(<a href='https://doi.org/10/dpvrft'>Sherlaw-Johnson, 2005</a>) `$$Vn=\sum\limits_{i=1}^ny_n - \sum\limits_{i=1}^n X_n$$` ] .pull-right[ <p style="text-align:center;"> <img src="./assets/img/vlad_limits.png" alt="SHMI VLAD chart for fluid an electrolyte disorders, taken from Oxford University Hospital board papers" width = "500" height="300"> </p> .footnote[Chart sourced from https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/about/trust-board/2018/january/documents/MRG2017.149a-shmi-update.pdf] ] --- class: inverse ## Summary + Mortality monitoring is common, but it's use as a global measure (rather than specific conditions) is unclear. + Not directly linked to avoidable deaths + Crude mortality can be sensibly used in some cases, but confounded by case-mix + Case-mix adjusted mortality is usually done by indirect standardisation, with regression model + SMRs as grouped sums of observed / 'expected' (or 'predicted') + HSMR was first national measure in UK - narrow scope and extensive case-mix adjustment + SHMI is NHS-owned indicator - wider scope and less case-mix adjustment + Criticisms remain of both - and SMRs broadly + Cross-sectional comparisons usually by funnel plot, longitudinal with cusums and vlad. -- __Worth knowing history and limitations of indicators before using them__ --- class: references ### References (1) <p><cite><a id='bib-blackAssessingQualityHospitals2010a'></a><a href="#cite-blackAssessingQualityHospitals2010a">Black, N.</a> (2010). “Assessing the Quality of Hospitals”. In: <em>BMJ</em> 340, p. c2066. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2066">10.1136/bmj.c2066</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-bottlePredictingFalseAlarm2011'></a><a href="#cite-bottlePredictingFalseAlarm2011">Bottle, A. and P. Aylin</a> (2011). “Predicting the false alarm rate in multi-institution mortality monitoring”. In: <em>The Journal of the Operational Research Society</em> 62.9, pp. 1711–1718. ISSN: 01605682, 14769360. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/cbr4rq">10/cbr4rq</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-campbellDevelopingSummaryHospital2012'></a><a href="#cite-campbellDevelopingSummaryHospital2012">Campbell, M. J., R. M. Jacques, J. Fotheringham, et al.</a> (2012). “Developing a summary hospital mortality index: retrospective analysis in English hospitals over five years”. In: <em>BMJ</em> 344, p. e1001. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/gb3r9t">10/gb3r9t</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-carequalitycommissioncqcNHSAcuteHospitals2014'></a><a href="#cite-carequalitycommissioncqcNHSAcuteHospitals2014">Care Quality Commission</a> (2014). <em>NHS acute hospitals: Statistical Methodology</em>. Care Quality Commission (CQC).</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-cecilWhatRelationshipMortality2020'></a><a href="#cite-cecilWhatRelationshipMortality2020">Cecil, E., A. Bottle, A. Esmail, et al.</a> (2020). “What Is the Relationship between Mortality Alerts and Other Indicators of Quality of Care? A National Cross-Sectional Study”. In: <em>Journal of Health Services Research & Policy</em> 25.1, pp. 13–21. ISSN: 1355-8196. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819619847689">10.1177/1355819619847689</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-cecilInvestigatingAssociationAlerts2018'></a><a href="#cite-cecilInvestigatingAssociationAlerts2018">Cecil, E., A. Bottle, A. Esmail, et al.</a> (2018). “Investigating the Association of Alerts from a National Mortality Surveillance System with Subsequent Hospital Mortality in England: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis”. In: <em>BMJ Quality &amp; Safety</em> 27.12, p. 965. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007495">10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007495</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-deeksEvaluatingNonrandomisedIntervention2003'></a><a href="#cite-deeksEvaluatingNonrandomisedIntervention2003">Deeks, J. J., J. Dinnes, R. D'Amico, et al.</a> (2003). “Evaluating Non-Randomised Intervention Studies.” In: <em>Health technology assessment (Winchester, England)</em> 7.27, pp. iii-173. ISSN: 1366-5278.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-girlingCasemixAdjustedHospital2012'></a><a href="#cite-girlingCasemixAdjustedHospital2012">Girling, A. J., T. P. Hofer, J. Wu, et al.</a> (2012). “Case-Mix Adjusted Hospital Mortality Is a Poor Proxy for Preventable Mortality: A Modelling Study”. In: <em>BMJ Quality & Safety</em> 21.12, pp. 1052–1056. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/f4fr3b">10/f4fr3b</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-goldsteinLeagueTablesTheir1996'></a><a href="#cite-goldsteinLeagueTablesTheir1996">Goldstein, H. and D. J. Spiegelhalter</a> (1996). “League Tables and Their Limitations: Statistical Issues in Comparisons of Institutional Performance”. In: <em>Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society)</em> 159.3, pp. 385–443. ISSN: 09641998, 1467985X. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/chf9kj">10/chf9kj</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-griggNullSteadystateDistribution2008'></a><a href="#cite-griggNullSteadystateDistribution2008">Grigg, O. and D. Spiegelhalter</a> (2008). “The null steady-state distribution of the CUSUM statistic”. In: <em>Technometrics : a journal of statistics for the physical, chemical, and engineering sciences</em>. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/bgvkdx">10/bgvkdx</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-hawkesHowMessageMortality2013'></a><a href="#cite-hawkesHowMessageMortality2013">Hawkes, N.</a> (2013). “How the Message from Mortality Figures Was Missed at Mid Staffs”. In: <em>BMJ : British Medical Journal</em> 346, p. f562. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f562">10.1136/bmj.f562</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-hoganAvoidabilityHospitalDeaths2015'></a><a href="#cite-hoganAvoidabilityHospitalDeaths2015">Hogan, H., R. Zipfel, J. Neuburger, et al.</a> (2015). “Avoidability of Hospital Deaths and Association with Hospital-Wide Mortality Ratios: Retrospective Case Record Review and Regression Analysis”. In: <em>BMJ</em> 351. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/gb3swm">10/gb3swm</a>.</cite></p> --- class: references ### References (2) <p><cite><a id='bib-iezzoniRisksRiskAdjustment1997'></a><a href="#cite-iezzoniRisksRiskAdjustment1997">Iezzoni, L. I.</a> (1997). “The Risks of Risk Adjustment”. In: <em>JAMA</em> 278.19, pp. 1600–7. ISSN: 0098-7484 (Print) 0098-7484 (Linking). DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/c2trv4">10/c2trv4</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-jarmanMonitoringChangesHospital2005'></a><a href="#cite-jarmanMonitoringChangesHospital2005">Jarman, B., A. Bottle, P. Aylin, et al.</a> (2005). “Monitoring Changes in Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratios”. In: <em>BMJ (Clinical research ed.)</em> 330.7487, pp. 329–329. ISSN: 1756-1833. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7487.329">10.1136/bmj.330.7487.329</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-jarmanExplainingDifferencesEnglish1999'></a><a href="#cite-jarmanExplainingDifferencesEnglish1999">Jarman, B., S. Gault, B. Alves, et al.</a> (1999). “Explaining differences in English hospital death rates using routinely collected data”. In: <em>BMJ</em> 318.7197, pp. 1515–1520. ISSN: 0959-8138 1468-5833. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/fkkfm9">10/fkkfm9</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-keoghKeoghReviewHospital2013'></a><a href="#cite-keoghKeoghReviewHospital2013">Keogh, B.</a> (2013). <em>Keogh Review on Hospital Deaths Published - NHSUK</em>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-lilfordUseMisuseProcess2004'></a><a href="#cite-lilfordUseMisuseProcess2004">Lilford, R., M. A. Mohammed, D. Spiegelhalter, et al.</a> (2004). “Use and Misuse of Process and Outcome Data in Managing Performance of Acute Medical Care: Avoiding Institutional Stigma”. In: <em>Lancet</em> 363.9415, pp. 1147–54. ISSN: 0140-6736. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/c97xd2">10/c97xd2</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-lilfordUsingHospitalMortality2010'></a><a href="#cite-lilfordUsingHospitalMortality2010">Lilford, R. and P. Pronovost</a> (2010). “Using Hospital Mortality Rates to Judge Hospital Performance: A Bad Idea That Just Won't Go Away”. In: <em>BMJ</em> 340, p. c2016. ISSN: 1756-1833 (Electronic) 0959-535X (Linking). DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/frq62g">10/frq62g</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-lovegroveMonitoringPerformanceCardiac1999'></a><a href="#cite-lovegroveMonitoringPerformanceCardiac1999">Lovegrove, J., C. Sherlaw-Johnson, O. Valencia, et al.</a> (1999). “Monitoring the Performance of Cardiac Surgeons”. In: <em>The Journal of the Operational Research Society</em> 50.7. Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan Journals, pp. 684–689. ISSN: 01605682, 14769360. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/dtsvbg">10/dtsvbg</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-maineyStatisticalMethodsNHS2020'></a><a href="#cite-maineyStatisticalMethodsNHS2020">Mainey, C.</a> (2020). “Statistical methods for NHS incident reporting data”. London. URL: <a href="https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10094736/">https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10094736/</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-marang-vandemheenSimpsonParadoxHow2014'></a><a href="#cite-marang-vandemheenSimpsonParadoxHow2014">Marang-van de Mheen, P. J. and K. G. Shojania</a> (2014). “Simpson's Paradox: How Performance Measurement Can Fail Even with Perfect Risk Adjustment”. In: <em>BMJ Quality &amp; Safety</em> 23.9, p. 701. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003358">10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003358</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-mohammedEvidenceMethodologicalBias2009'></a><a href="#cite-mohammedEvidenceMethodologicalBias2009">Mohammed, M. A., J. J. Deeks, A. Girling, et al.</a> (2009). “Evidence of Methodological Bias in Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratios: Retrospective Database Study of English Hospitals”. In: <em>BMJ</em> 338, p. b780. ISSN: 1756-1833 (Electronic) 0959-535X (Linking). DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/bv4sh8">10/bv4sh8</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-nichollCasemixAdjustmentNonrandomised2007'></a><a href="#cite-nichollCasemixAdjustmentNonrandomised2007">Nicholl, J.</a> (2007). “Case-Mix Adjustment in Non-Randomised Observational Evaluations: The Constant Risk Fallacy”. In: <em>Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979-)</em> 61.11, pp. 1010–1013. ISSN: 0143005X, 14702738. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/d7f9jh">10/d7f9jh</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-sherlaw-johnsonMethodDetectingRuns2005'></a><a href="#cite-sherlaw-johnsonMethodDetectingRuns2005">Sherlaw-Johnson, C.</a> (2005). “A Method for Detecting Runs of Good and Bad Clinical Outcomes on Variable Life-Adjusted Display (VLAD) Charts”. In: <em>Health Care Management Science</em> 8.1, pp. 61–65. ISSN: 1572-9389. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/dpvrft">10/dpvrft</a>.</cite></p> --- class: references ### References (3) <p><cite><a id='bib-skellamProbabilityDistributionDerived1948'></a><a href="#cite-skellamProbabilityDistributionDerived1948">Skellam, J. G.</a> (1948). “A Probability Distribution Derived from the Binomial Distribution by Regarding the Probability of Success as Variable Between the Sets of Trials”. In: <em>Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological)</em> 10.2, pp. 257–261. ISSN: 00359246.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-spiegelhalterFunnelPlotsComparing2005'></a><a href="#cite-spiegelhalterFunnelPlotsComparing2005">Spiegelhalter, D. J.</a> (2005a). “Funnel plots for comparing institutional performance”. In: <em>Statistics in Medicine</em> 24.8, pp. 1185–202. ISSN: 0277-6715 (Print) 0277-6715 (Linking). DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/fq7z8t">10/fq7z8t</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-spiegelhalterStatisticalMethodsHealthcare2012'></a><a href="#cite-spiegelhalterStatisticalMethodsHealthcare2012">Spiegelhalter, D., C. Sherlaw-Johnson, M. Bardsley, et al.</a> (2012). “Statistical methods for healthcare regulation: Rating, screening and surveillance”. In: <em>Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society)</em> 175.1, pp. 1–47. ISSN: 09641998. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/dqpqpk">10/dqpqpk</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-taylorStandardizedMortalityRatios2014'></a><a href="#cite-taylorStandardizedMortalityRatios2014">Taylor, P.</a> (2014). “Standardized Mortality Ratios”. In: <em>International Journal of Epidemiology</em> 42.6, pp. 1882–1890. ISSN: 0300-5771. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10/f5pxfw">10/f5pxfw</a>.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-wedderburnQuasiLikelihoodFunctionsGeneralized1974'></a><a href="#cite-wedderburnQuasiLikelihoodFunctionsGeneralized1974">Wedderburn, R. W. M.</a> (1974). “Quasi-Likelihood Functions, Generalized Linear Models, and the Gauss-Newton Method”. In: <em>Biometrika</em> 61.3, pp. 439–447.</cite></p> <p><cite><a id='bib-wrightLearningDeathHospital2006'></a><a href="#cite-wrightLearningDeathHospital2006">Wright, J., B. Dugdale, I. Hammond, et al.</a> (2006). “Learning from Death: A Hospital Mortality Reduction Programme”. In: <em>Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine</em> 99.6, pp. 303–308. ISSN: 0141-0768. DOI: <a href="https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.99.6.303">10.1258/jrsm.99.6.303</a>.</cite></p>